An example of a true sponge city project. Sanya Dong’an Wetland Park, Sanya, Hainan Province, China

Two recent articles in the American media — one from The New York Times and another from The Christian Science Monitor — raised questions about the efficacy of China’s sponge city concept in the face of climate change. As storms become more powerful and release more water faster, the flood control mechanisms of Chinese cities are being overrun. News stories have focused on recent dangerous flooding in Zhengzhou, a city of 12 million on the banks of the Yellow River, which killed more than 300 people and trapped others in tunnels and subways. The articles questioned whether nature-based solutions, rooted in the sponge city approach, can handle the increasing amounts of stormwater inundating Chinese cities on rivers and coasts.

In a Zoom interview, Kongjian Yu, FASLA — founder of Turenscape, one of China’s largest landscape architecture firms, and creator of the sponge city concept — said, “first of all, Zhengzhou is not a true sponge city. There has still been way too much development and grey infrastructure.” And many Chinese cities have been using the term “sponge city as a political slogan” and a way to attract central government funding, given the deep support for the approach from Chinese president Xi Jinping.

He believes the benefits of the sponge city approach, which involves designing and constructing city-wide systems of ponds, wetlands, and parks that retain stormwater, have been proven. “Since ancient times, Chinese cities along the Yellow River with monsoon climates have used ponds to manage flooding and stormwater. So we know these approaches worked for over 2,000 years because these cities survived.”

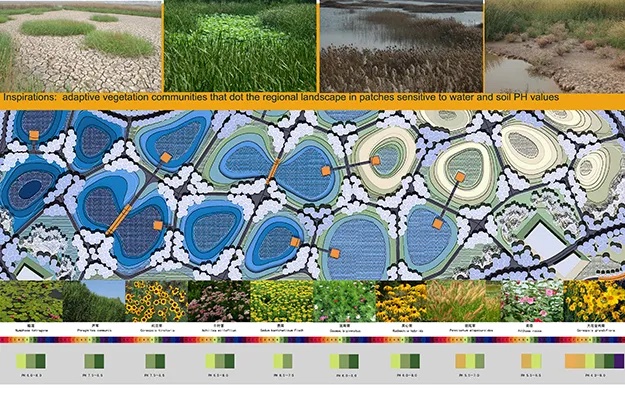

ASLA 2010 Professional General Design Honor Award. Tianjin Qiaoyuan Park: The Adaptation Palettes. Tianjin City, China / Turenscape

ASLA 2010 Professional General Design Honor Award. Tianjin Qiaoyuan Park: The Adaptation Palettes. Tianjin City, China / Turenscape

ASLA 2010 Professional General Design Honor Award. Tianjin Qiaoyuan Park: The Adaptation Palettes. Tianjin City, China

Chinese cities today are required to maintain 30 percent of the city as green space. Another 30 percent is dedicated to community space. For Yu, this means there is more enough space to create more ponds and water-absorbing parks that can capture vast amounts of water. “In 60 percent of the land in cities, we can use nature to retain water so it doesn’t drain away. In China, we have a saying — ‘water is precious, don’t let it go.’ There is plenty of space to be used to retain water.”

ASLA 2012 Professional General Design Award of Excellence. A Green Sponge for a Water-Resilient City: Qunli Stormwater Park. Haerbin City, Heilongjiang Province, China

Yu outlined the key components of the sponge city approach. Stormwater should be captured using green infrastructure at its source, where it falls. Sponges should be evenly distributed and permeable so they can absorb water instead of shifting it somewhere else. “If properly designed, it’s a democratic water management system” made up of very local solutions.

Yu claims that with the story of Zhengzhou, the “media is seeking conflict and targeting something that isn’t a sponge city. Sponge cities can only solve the problem. We need more sponges, not less.”

Despite a recent video of a talk he gave, which he says has been viewed by more than 100 million Chinese citizens, there still needs to be more public education about the benefits of sponge cities. “Some of the public still doesn’t understand the sponge city concept, and some may find it a waste of money. Furthermore, some civil and hydrological engineers in China have been attacking the sponge city, nature-based approach because it takes away their jobs.”

If a sponge city is working as it should, “there would be no flooding. People forget when they don’t have disasters.”

When asked about NYC’s new approach to handling sea level rise-induced flooding in lower Manhattan, which will involve constructing a sea wall along with large-scale cisterns to store water, he said: “cisterns are unsustainable.” The concrete cisterns “have to be huge and therefore expensive and high maintenance.” Furthermore, this approach wastes water, which is a “living resources and when combined with plants and soils creates more natural resources.”

Yu calls for greater capacity building among the landscape architecture and civil engineering professions in China and elsewhere in the sponge city concept. “The issue in China is that some designers and engineers are building parks but not building in the stormwater management capacity needed.” In China, stormwater is still the responsibility of civil and hydrological engineers.

To address issues with the design and implementation of sponge cities, Yu will be hosting a summit with the leadership of the civil and hydrological engineers at his research and educational campus. “We will have a high-level discussion aimed to bridge the gaps.”

Furthermore, Yu’s team is publishing a new book in Mandarin — Performance Study of Designed Ecologies — that includes real data about sponge city projects. In addition to his videos, he has also produced a textbook for China’s thousands of mayors, who he said are on board with the approach.

“Flooding in the era of climate change presents an opportunity for landscape architects. We have an opportunity to build up our approach. Landscape architects can solve these problems — not with concrete pipes and cisterns — but with nature.”

ASLA 2020 Professional General Design Honor Award. Deep Form of Designed Nature: Sanya Mangrove Park, Sanya City, Hainan Province, China.